Guidelines Vs Reality: The Work Experiences of Assistant Psychologists and Honorary Assistant Psychologists in the UK

The following piece is by Tori Snell, Consultant Clinical Psychologist and Joint Director for England, and Ruby Ramsden, Senior Assistant Psychologist. It describes a study of the experiences of Assistant Psychologists and Honorary Assistant Psychologists (APs and HAPs) working in NHS, third sector and private services across the UK. The study was part of establishing procedures for such posts within their place of work – a national charity with a growing number of AP roles. An article about the study is in preparation by R. Ramsden, J. Croca, G. Caetano, S. Thomas, R. Jenkins, M. Wang, and T. Snell.

Guidelines Vs Reality: The Work Experiences of Assistant Psychologists and Honorary Assistant Psychologists in the UK

Background

Over the past decade, the work context for UK-based Assistant Psychologists (APs) and Honorary Assistant Psychologists (HAPs) has changed considerably. HAP roles are more common than before. It is no longer unusual to see these advertised as unpaid full-time posts. Supervision of APs is not always by qualified Psychologists; and, the clinical risks to which both are exposed seem to increase with time as the cuts to mental health services deepen. Enough has been written to highlight these trends over many years (Rezin &Tucker, 1998; Williams, 2001; Woodruff & Wang, 2005; Byrne and Towney, 2011; Acker, Gilligan et al., 2013; Stevens, Whittington et al.,2015; Douglas, Trevethan et al., 2018). What has not kept pace are the systems and procedures for ensuring (1) that people who access services are not put at risk by staff who are being asked to undertake work for which they are not trained and competent, and (2) that APs and HAPs, who are highly motivated to demonstrate their willingness to work hard and their readiness to enter professional training, are not improperly used as a substitute for qualified staff.

Study rationale

The current study was initiated following a query by non-psychology colleagues, involved in a national, community-based mental health pilot, who wished to know the number of 1:1 Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT) sessions an AP could offer per week. The question was reflected to them: ‘how many do you understand it to be’? The answer should not have surprised us. However, it did because it was based on their experiences of NHS services with APs. The answer was twenty. In other words, their expectation was that APs would have an average of four clinical appointments five days a week. These were reasonable colleagues with what they believed were reasonable expectations. As part of the discovery process for the creation of policy and guidelines within our organisation, a survey was launched to gain an understanding of AP and HAP roles and responsibilities within the UK and to see if these aligned with existing professional guidelines (BPS, 2007; BPS, 2016). At the time of the survey, the organisation had four APs and one ‘pilot’ HAP volunteering for three hours a week alongside her full-time role within the organisation. The idea was to define the correct conditions for the fair allocation of roles and responsibilities for APs and for HAPs.

What we did

Following a review of the proposal by our organisation’s research oversight group, which has on it two academics from the University of Manchester, two surveys were shared on five psychology social media groups: one survey for APs and one for HAPs. Participants were informed as to the purpose of the surveys and assured anonymity. These were live from 16 July to 16 September 2019. In total, 228 responded (n=209 APs; n=19 HAPs).

What we learned

Responses suggest that at least 27% of participants’ working practices were not in line with existing BPS guidance for APs and HAPs (BPS, 2007; BPS, 2016).

Key findings include:

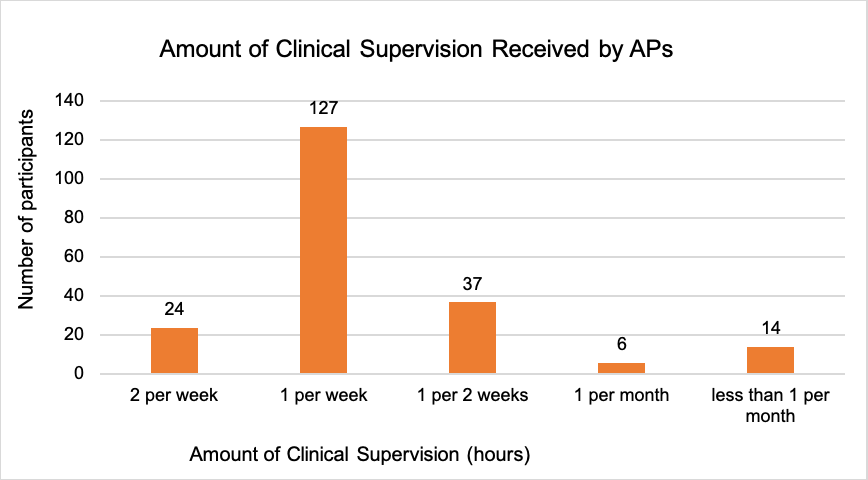

- 27.3% of APs reported receiving less than one hour of clinical supervision per week.

- 4.8% of APs and 15.8% of HAPs reported receiving clinical supervision from a non-psychologist or receiving none at all.

- 27.7% of APs reported taking on activities beyond the role of an AP.

- 15.8% of HAPs reported volunteering full-time.

- 35.5% APs and 31.6% HAPS reported dissatisfaction relating to their roles. Common themes for role dissatisfaction included ‘burn out’ and ‘too much responsibility’ for APs, and ‘financial burden’ for HAPs.

Findings also suggest that the employment experiences and responsibilities of APs and HAPs vary considerably, indicating that there is a need for development of clear guidance in some areas. For example, some APs reported not seeing any service users on a 1:1 basis and others reported seeing over 20 per week; some APs and HAPs reported working with people presenting with high risk (suicidal) behaviours on their own; and some HAPs facilitated 1:1 and group sessions without another member of staff to support them. The existing professional guidelines, some of which are more than ten years out of date, do not explicitly address whether these experiences are considered appropriate for APs or HAPs.

Why we think there is a need for professional standards

The wellbeing and safety of people who access mental health services is central to why clear and up-to-date guidelines should be a minimum expectation for the psychology profession. How the professional standards are set can make a difference to the experiences of our most junior colleagues, who may aspire to become qualified psychologists and should be afforded the appropriate level of clinical supervision and support to work safely and gain the learning needed to progress in the field. Guidelines are there to quality assure certain fundamental aspects of pre-qualified roles. These have the potential to influence the path that remains so largely inaccessible to people from minority backgrounds and those from marginalised communities. However, up-to-date professional standards are no solution in the absence of strong leadership and investment in the services where APs and HAPs work.

Doing things better

In our own place of work, we realised that the expectation from non-psychology managers and stakeholders, which had prompted us to conduct a national survey would likely be encountered again in our many other services and that the existing guidelines (BPS, 2007) were no longer a helpful starting point. Our survey findings returned us to Woodruff and Wang (2005) who cautioned that too often (intentionally or unintentionally) APs/HAPs and their supervisors conspire to over-estimate the assistant’s experience and competency because: (1) the assistant is desperate to demonstrate their clinical abilities in their subsequent applications to DClinPsy training courses; and (2) clinical pressure on supervisors increases the temptation for them to allocate inappropriately complex clinical work to the assistant. This is not what we want for our junior psychology colleagues. The consequent guidelines and policy we have drafted for our organisation stem from the efforts of the five main authors (four APs and one HAP) who evaluated their own roles and responsibilities in the context of national trends reported by their peers and against the existing guidelines (BPS, 2007; BPS 2016). We think the results of their work will improve the experience of people who access our services; help us to communicate better with stakeholders and non-psychology colleagues about roles that involve APs; and will support our APs and HAPs to have the best possible opportunities to grow personally and professionally. We want our APs and HAPs to feel able to speak out and seek support if they feel the guidelines are not being adhered to. As we understand, there is no regulating body that exists in the UK to help APs and HAPs manage the sorts of difficulties our survey findings highlighted.

What we missed

The purpose of the current study was to understand the work experiences of APs and HAPs so as to inform our working practice. The two surveys used did not capture important demographic information relating to race, ethnicity, disability, or socio-economic factors. This is a significant shortcoming. Not having clear and current guidance for APs, the increase in HAP posts – and now also ‘year in industry’ placements during undergraduate study (BPS, 2016) – risks the institutional exploitation of psychology undergraduates and postgraduate assistants. This form of exploitation, however unintentional, must be understood as a significant contributing factor for why the profession is characterised by a lack of diversity (Turpin & Coleman, 2010; BPS, 2016) – including the under-representation of minority psychologists and trainees (Turpin & Coleman, 2010) as well those from economically underprivileged backgrounds. Consider the fact that 81% of total applicants for the Doctorate in Clinical Psychology in 2017 were white and 19% were ethnic minorities. Despite this, 88.1% of successful applicants were white and only 11.9% ethnic minorities (“Clearing House for Postgraduate Courses in Clinical Psychology Equal Opportunities Data for 2017 Entry”, 2018).

What we recommend

- Guidelines for Assistant Psychologists should include more specific directives concerning appropriate clinical activity and limitations.

- Guidelines for Honorary Assistant Psychologists should include clear guidance as to what roles and responsibilities HAPs can and cannot perform.

- The importance of reading and adhering to such professional guidelines is highlighted to all pre-qualified and qualified psychologists.

- Clinical psychologists in managerial positions should ensure that all APs and HAPS in their services are properly supervised so that staff and the people who access services are not put at risk.

- Professional bodies, such as the British Psychological Society (BPS) or the Association of Clinical Psychologists – UK (ACP-UK) should ensure that the guidelines for our profession remain abreast of trends through regular review and through active consultation, including from experts by experience, to ensure equity, diversity and inclusion is a central principle of widening access to our profession.

References

Acker, L., Gilligan, L. and Cooper, S. (2013). The price of ‘free’ – Thoughts on the role of Honorary Assistant Psychologists. Clinical Psychology Forum, 248, 46–48

British Psychological Society (2007). Guidelines for the employment of assistant psychologists. Leicester, UK: BPS.

British Psychological Society (2016). Position statement and good practice guidelines: Applied practitioner psychologist internship programmes and unpaid voluntary assistant psychologist posts. Leicester, UK.

Byrne, M. and Twomey, C. (2011). Volunteering in psychology departments–Quid pro quo? The Irish Psychologist. 38, 75-82.

Douglas, C., Trevethan, C. and Summers, F. (2018). The Expectations and Experience of Honorary Assistant Psychologists in NHS Grampian: An Audit. MSc. University of Aberdeen.

Rezin, V. & Tucker, L. (1998). The uses and abuses of assistant psychologists: a national survey of caseload and supervision. Clinical Psychology Forum, 115, 37-42.

Stevens, D., Whittington, A., Moulton-Perkins, A. & Palachandran, V. (2015). Voluntary psychology graduate internships: Conveyor belt of exploitation or stepping stone to success? Clinical Psychology Forum, 270, 34-39.

Turpin, G., & Coleman, G. (2010). Clinical psychology and diversity: Progress and continuing challenges. Psychology Learning & Teaching, 9(2), 17-27.

Williams, W. (2001). Relevant experience: Alternatives to the assistant psychologist post? The Psychologist, 14, 188-189.

Woodruff, G. & Wang, M. (2005). Assistant psychologists and their supervisors: Role or semantic confusion. Clinical Psychology, 48, 33-36.