ACP-UK Rapid Response: Parliamentary Call for Evidence on Delivering Core NHS and Care Services During the Pandemic and Beyond

The Health and Social Care Committee of the House of Commons is made up of MPs from the main political parties. It scrutinises government and in particular the work of the Department of Health and Social Care. It also scrutinises the work of public bodies in the health system in England, such as NHS England and Improvement, Public Health England and the Care Quality Commission (health services in Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales are the responsibility of their respective governments).

It does so by holding inquiries on specific topics and accountability hearings with the Secretary of State, and Chief Executives of relevant public bodies. The Committee asks questions and gathers evidence, listens to witnesses, draws conclusions, makes recommendations, and holds health and social care leaders to account for their actions.

One of its current inquiries is about “Delivering core NHS and care services during the pandemic and beyond.” It called for written evidence (maximum 3,000 words) which had to be submitted by 8th May. Once the written evidence has been assessed, the Committee will decide which witnesses to invite to provide oral evidence. That is when individuals answer the Committee’s questions and provide their opinion, usually during public sessions.

Inquiries usually conclude with the publication of a report containing the Committee’s findings and its conclusions, as well as recommendations to the Government and/or other public bodies. The Committee then expects to receive a response from the Government to the recommendations, in principle within two months.

We decided to submit evidence to this inquiry because the pandemic has already had profound effects on health and social care services. The call for evidence implies that there is a real need for fresh thinking about how to address the challenges ahead. The timescale for producing the evidence was very short, just 2 weeks from the Call for Evidence to the closing date. Our evidence was therefore based on the suggestions of members of the Board of Directors.

Addendum

Owing to the 3,00 word limit it was not possible to include everything that we might have wanted to say.

Download the document here or read it below.

Evidence to the House of Commons Health and Social Care Committee

concerning

Delivering Core NHS and Care Services during the Pandemic and Beyond

The Association of Clinical Psychologists U.K. is a country-wide not-for-profit Community Interest Company and professional body. We promote, publicise, support and develop the contributions of clinical psychologists, a well-established and highly trained NHS profession, to improving the health and social care and well-being of the population of the United Kingdom.

SUMMARY OF OUR EVIDENCE

We welcome this opportunity to offer proposals concerning the upcoming strategic challenges identified by the Committee. Our evidence focuses on those post-pandemic issues concerned with recovery and rehabilitation to which we believe clinical psychology and clinical psychologists can make particular contributions.

We propose that

- in order to retain the positive changes arising from the pandemic, this is the time to bring about an important cultural change in the perceptions of services;

- health and social care should be seen as a democratically controlled integrated system of community-based services, against a background of supporting hospitals and specialist health services;

- there are two transitional measures which will facilitate answers to the ‘How to’ questions identified by the Committee: the use of the human life cycle as the framework for giving coherence to planning the totality of health and social care; and the creation of a single electronic Life Journey Record for each person, accessible by all agencies when providing their health and social care;

- existing work on community and organisational clinical psychology interventions in communities that create sustainable change should be developed further;

- the Committee should recommend psychological and other research to identify the limits of remote services, and in particular what kinds of face-to-face services should be preserved and protected;

- noting that the major NICE recommended treatments for disorders resulting from trauma are psychological treatments developed by clinical psychologists, clinical psychologists have the training and expertise to lead the provision of those services;

- NHS management should investigate recruiting extra staff from the pool of independent clinical psychology practitioners;

- amongst the steps that should be taken to prevent avoidable stress amongst NHS staff is a psychologically informed approach to leadership and communications;

- a Chief Psychological Professions Officer should be appointed to the senior management of the NHS in each nation as a matter of urgency;

- all NHS Trusts should appoint a Director of Psychological Services with membership of the Executive Board of the Trust.

INTRODUCTION: WHO WE ARE

- Clinical psychology is an integration of behavioural science, psychological theory, and clinical skills applied to the needs of the health, social and community care services. It is not just concerned with mental health and psychological therapies. Clinical psychologists can be found throughout specialist hospital, primary health care, community and residential care services, promoting effective evidence-based interventions and quality of care.

- Clinical psychologists typically qualify between 25 and 35 years of age, having achieved a Doctorate in Clinical Psychology, following at least 7 years of training. The training consists of a degree in psychology and post-graduate training which includes supervised clinical experience in all phases of the life-span. There are 13,500 clinical psychologists registered with the Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC).

- Experienced clinical psychologists provide clinical leadership through their own evidence-based practice and by teaching, supervising and supporting the work of others. Many are innovative, developing applications of psychology and related disciplines to solve identified clinical needs. Some also design, develop and / or support services to implement those and other innovations.

Preserving positive change and achieving appropriate balance

- Hospital-based specialist services have inevitably been the focus of attention during the acute phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. They are likely to remain a focus for the immediate future (“Meeting the wave of pent-up demand for health and care services that have been delayed due to the coronavirus outbreak”.)

- However there is ample evidence that viral diseases in general, and those resulting in life-threatening experiences in particular, often leave people with significant physical and psychological deficits and chronic mental health problems. These range, for example, from post-viral fatigue, episodes of cognitive impairment, depression, to post-traumatic stress disorder and permanent detrimental changes in the sense of self and purpose in life.

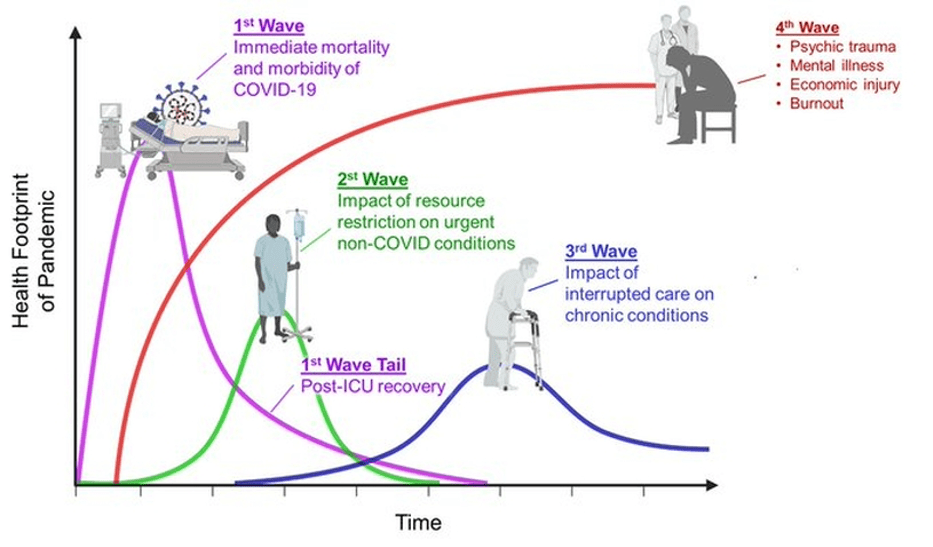

- Most of the health and care consequences of the pandemic will occur and require services outside hospitals, and may last for many months, even years. (The following graphic by Dr Victor Tseng [Twitter #VectorSting] helped us to recognise some of the consequences for post-pandemic services.)

- Most people’s experience of health and social care is of the organisational patchwork of ‘community-based’ services in their own locality. From their point of view hospitals and hospital-based services are an exceptional addition to their local services, and are often less easy to reach and use than those services.

- Although there have been many ‘community based’ developments over the last 70 years (such as primary care teams, replacement of institutions, commercial residential care for older and disabled people, and community outreach from various specialist services) they have often been unco-ordinated and underfunded.

- Consequently, the patchwork totality of community-based services is ill-equipped to respond to the increased and potentially long term demands that are going to be placed on it. Not only may the quantity of those services be inadequate but the usual high quality of care may be diminished as well.

- We propose that in order to retain the positive changes arising from the pandemic, this is the time to bring about an important cultural change, a change in how health and social care services are perceived and understood.

- Culture change requires both an awareness and acceptance that something is not working as it should be, and alternative ways of thinking and acting which those affected either find convincing or are obliged to accept. Many people, when they think about the NHS and social care, focus on hospitals seen against a background patchwork of community-based services. The cultural change that we propose is a reversal of this emphasis, such that we all see health and social care as a democratically controlled integrated system of community-based services, against a background of supporting hospitals and specialist health services.

- It is implicit in this conception of health and social care that services should respond to the needs of natural communities. Some of these needs, such as health inequalities, may be specific to that area of the country. Others, such as post-pandemic problems, may be shared with the rest of the country.

- This cultural change, i.e. reframing understanding of health and social care by focusing primarily on the system of community-based services within geographical localities, would preserve and build on the lessons learned during this pandemic about the complex inter-relationships of causes and services.

- We also believe that by taking account of the reality of most peoples’ everyday interactions with those services, that change would generate planning that place the needs of patients and their families at the centre of such planning.

- Current community-based services are a patchwork because of different sources of ownership, management, funding and commissioning. Ideally, they should be brought into a seamless democratically controlled integrated system. But that would require legislative and organisational changes which may be too ambitious at present. Therefore, we propose two transitional measures which we believe will facilitate answers to the two ‘How to’ questions identified by the Committee.

The Human Life Cycle

- Firstly, we propose the human life cycle as the framework for giving coherence to planning the totality of health and social care. It may be thought that this is what is done already. But the truth is that much planning is based on diseases, disorders and the provision of technical services. Contrary to that, research has demonstrated the significant impacts on health and longevity of, for example, a secure and stable childhood, a person’s position in society, economic factors, childhood deprivation and trauma, adult unemployment and loneliness in old age.

- The over-representation of COVID-19 sickness and death in (for example) the BAME population, found during the acute phase of the pandemic, may be a consequence of the impact of social inequality on health and needs urgently to be investigated. Referring to the Committee’s concern with ‘Meeting the needs of rapidly discharged hospital patients with a higher level of complexity’ and ‘Providing healthcare to vulnerable groups who are shielding’, successful recovery and rehabilitation is also likely to be linked to socioeconomic and psychological factors.

- One of clinical psychologists’ basic skills is formulating an account of the interactions between different aspects of a person’s life including their physical state, life circumstances and relationships, with the aim of identifying effective interventions. We propose that there should be easier access to clinical psychologists’ expertise for GPs, community nurses, other community staff and schools; one way of doing that is described in paragraph 39 of this evidence.

- Our proposals also draw on existing work on community and organisational clinical psychology interventions in communities; those interventions can create sustainable change. We propose that they should be developed further.

- Identifying the services available to a person on their journey through life, with associated costs and benefits, would help the public to understand what services are available, and recognise the lifelong benefits of a stable, secure childhood. We anticipate that presenting service information in relation to the life cycle would help to create the support necessary to fund those services and prioritise them when necessary.

A Life Journey Record

- Secondly, we propose that some of the benefits of a whole system approach to services linked to the human life cycle could be achieved by creating a single electronic Life Journey Record for each person. Importantly, the record would be owned by the person to whom it refers, and they would be able contribute to it. We envisage that it would incorporate their existing primary health care records and would be accessible to all agencies at the time of providing health and social care. That would mean that irrespective of which agency was serving a person’s needs or where the service was based, those providing the services could inform themselves about that person’s needs and wishes, and contribute to the continuity of their care.

- This proposal, which builds on the benefits of emerging technologies, is consistent with the NHS’ drive to interoperable information systems, with important developments in localised information sharing, and with the concept of a ‘community of care’.

Identifying and addressing the limits of remote treatments and therapies

- Owing to the implementation of social distancing, self-isolation, shielding and ‘lockdown’ there has been a dramatic increase in the provision of ‘remote’ services i.e. provided through video or audio links.

- Remote services have been a way of maintaining service provision during the acute phase of the pandemic but, anecdotally, they have also been found to be cheaper whilst at the same time remaining effective. We therefore anticipate that there will an expectation, even pressure, to maintain such services in the future, replacing face to face services.

- However, there is little or no public information about the numbers and proportions of patients who cannot, or are unwilling to use remote services. We propose that needs to be investigated with a view to assuring the quality of care they receive.

- Some of the drivers of demand for healthcare, particularly in primary health care and A&E, are a person’s perceptions of changes in their body state (is a particular sensation a symptom or just a passing experience?), fear, pain, and expectations about the likely professional response to help-seeking. These are subjective states which do not necessarily reflect the nature or severity of any underlying disease or disorder. In the absence of symptoms a person may not seek help when they should, but sometimes fear or transient pain leads them to seek help when they do not need to do so. Whereas there is psychological and other research about the relationship between those factors and, for example, consulting one’s GP, little is currently known about whether the same relationships apply to remote services. Do remote services help or hinder early detection and intervention in disease processes? Is a person more likely to seek help appropriately if access to the service is via a video or audio link, or less likely?

- This is not a trivial matter. Concern about larger than expected reductions in attendances at A&E during the pandemic and professional concern about whether people are failing to seek help with potentially serious health conditions has already been reported by the media.

- It is also self-evident that some services cannot be provided remotely and require the patient’s physical presence in the service setting. That may change as remote sensing technologies are developed but the Committee’s concerns over cancer services, maternity services and mental health services including dementia suggest that it already recognises the potential for problems.

- Importantly, there is no substitute for the wealth of clinically relevant information that can be gained from a patient’s body language, appearance and social circumstances during face-to-face contact.

- We propose that the Committee should recommend psychological and other research to identify the limits of remote services, and in particular what kinds of face-to-face services should be preserved and protected.

Meeting extra demand for mental health services as a result of the societal and economic impacts of lockdown

- Under this heading we address some issues concerning psychological care and therapies for NHS and care staff, survivors of COVID-19 and their families, and those who are indirect victims of the pandemic such as those who have lost close relatives or friends or become unemployed or homeless.

- Directors of ACP-UK are already in discussions with senior management in the NHS in each of the four nations concerning the provision of NHS psychological therapy services to staff and patients.

- The major NICE recommended treatments for disorders resulting from trauma are psychological treatments developed by clinical psychologists. We propose that clinical psychologists have the training and expertise to lead those services.

- ACP-UK itself has launched a small-scale programme of support for psychologists seeking help and support concerning their COVID-19-related work and another for the benefit of doctors and senior managers. As an organisation, ACP-UK does not have the resources to offer services to people who are not health or social care staff but many clinical psychologists employed in the NHS have the capacity and skills to offer therapies to post-COVID-19 patients and their families.

- Looking after the psychological health of the NHS workforce is going to be key to enabling many staff to keep working. Experience to date has shown that a wide range of staff would want and use supportive interventions and, in some cases, psychological therapies as well.

- Through the services we have been offering we know that the recent exceptional demands of clinical work has not been the only source of severe stress. Some staff have experienced chaotic and inconsistent communications from the top of the Service downwards, across Trusts and across services. Staff in different Trusts and departments are being told to do completely different things concerning safety, remote working, which IT platform to use, etc. The guidance they are given may not make sense to them and creates confusion, inefficiency and loss of trust in management.

- We propose that amongst the steps that could be taken to prevent avoidable stress are psychologically informed approaches to leadership and communication, including a commitment to compassionate management and psychological safety at work. We also know that leaders themselves need time, space and support, to develop consistent thought-through messages to staff and to ensure that what is said is actually done.

- Since a major part of the work of NHS Occupational Health Services is going to be concerned with psychological and mental health issues, our general view is clinical psychologists should be fully integrated members of those services and could often lead them. However, that may not be possible where those services have been out-sourced to private companies. Further, even if psychological interventions are offered, some people and groups of staff are less likely to take them up either out of preference or because they cannot be released from their work commitments – a ‘one size fits all’ approach does not meet the need.

- There are also many keyworkers outside the NHS (for example in residential and domiciliary social care and in third sector organisations) and their needs must also be considered. In some places easy access to psychological care and services would be facilitated by co-locating those services near a large health centre or GP practice.

- However, the longstanding excess of demand over the capacity to provide NHS psychological services (particularly at step 4 of the ‘stepped care model’) remains a serious problem. Seeking to ameliorate the shortage by offering remote and digital services and by providing extra training and supervision to existing NHS staff are limited solutions; but ultimately additional fully trained staff are needed.

- Owing to shortage of some types of NHS posts there has been a growth in independent clinical psychology services in recent years. The practitioners were all trained by the NHS and most continue to be registered with HCPC. They represent a reservoir of experience and expertise which might be drawn upon during the next phase of the pandemic. We propose that NHS management investigate the possibilities of recruiting independent practitioners or providing some services through them.

- A current problem in improving the provision of NHS psychological care is the absence of clinical psychologists in the senior management of the Service and Trusts. Without posts for experienced advisors from the profession, managers cannot access the requisite expertise concerning the potential service benefits that could be on offer. We propose that a Chief Psychological Professions Officer should be appointed to the senior management of the NHS in each nation as a matter of urgency. Also we propose that all Trusts should appoint a Director of Psychological Services with membership of the Executive Board of the Trust.